BY NATALIE FIERTZ

As 2020 came to a close, the world looked back on a global pandemic, protests, lockdowns, and economic turmoil. Looking forward to the new year did offer some measure of hope; an array of vaccines had been developed and begun to be administered, but the crisis remained (and remains today) far from over. This is the vantage point of the 2021 Fragile States Index (FSI), based on data from an almost unprecedented year and assessing the social, economic, and political effects across 179 countries.

While it is far too soon for a comprehensive analysis of a phenomenon which touched every corner of the globe, and impacts that will reverberate for years, the FSI can help illustrate some key patterns and trends that are already identifiable. The first, and perhaps most obvious, of these is that many of the assumptions and beliefs that were widely held before the pandemic were not borne out and must now be reassessed at a fundamental level. Second, the pandemic was not a shock only to public health systems but instead both impacted, and was itself shaped by, economic, political, and security considerations. Third, while COVID-19 often dominated our collective attention, other long-term pressures did not sit idly by but continued to have their own effects, in ways both expected and unforeseen.

Before the pandemic, certain countries were widely believed to have greater capacity to prevent and manage large risks, often explicitly including public health threats. These beliefs were often founded largely on explicit or implicit models emphasizing economic wealth and technical expertise. Many of these wealthy and developed countries, however, have been among the most severely impacted by the pandemic and have had their fragilities and fault lines clearly exposed. Others, including those too often sidelined or ignored, have demonstrated a remarkable resilience from which the rest of the world can and should learn.

Just as the pandemic upended preconceptions about a binary dividing line between countries that were fragile and those that were not, so too did it shatter any notion that its consequences and the response effort could be confined within the bounds of public health. Beyond the health sector, the economic effects were among the most immediately apparent as global lockdowns contributed to plunging oil prices, disrupted supply chains, and the world economy crashed into a recession, with GDP contractions in many places substantially steeper than following the 2008 economic crisis. As the year progressed, the ripples of the pandemic’s direct and indirect effects spread further outward, reaching into more areas of public and private life. It also served in some cases as the first domino in a chain of events that ignited more longstanding and deep-seated grievances. The responses to the pandemic were also not simply a function of deploying public health resources as efficiently as possible but instead depended on social, economic, political, informational, and ethical factors.

Although the pandemic at times appeared to drive other issues off the front pages and down the priority list, the challenges that preceded it did not simply go away. The beginning of 2020 saw devastating wildfires in Australia which, combined with flooding, storms, and other fires, make clear that climate change cannot be ignored or minimized. The impacts of that crisis and of environmental degradation more broadly are increasingly recognized as being intertwined with fragility, a connection most plainly visible in the Sahel where violence continued to worsen in 2020. In other contexts, domestic and international situations that appeared to be largely frozen in place despite entrenched divisions exploded in dramatic and sometimes literal fashion, perhaps best exemplified by Lebanon and the Caucasus.

These three broad findings demonstrate the way that tools such as the FSI can offer the greatest value. That Yemen, Somalia, and Syria are faced with serious challenges is likely not new information. The FSI can help, however, surface high-level patterns, long-term trends, and unexpected results that prompt deeper investigation and analysis.

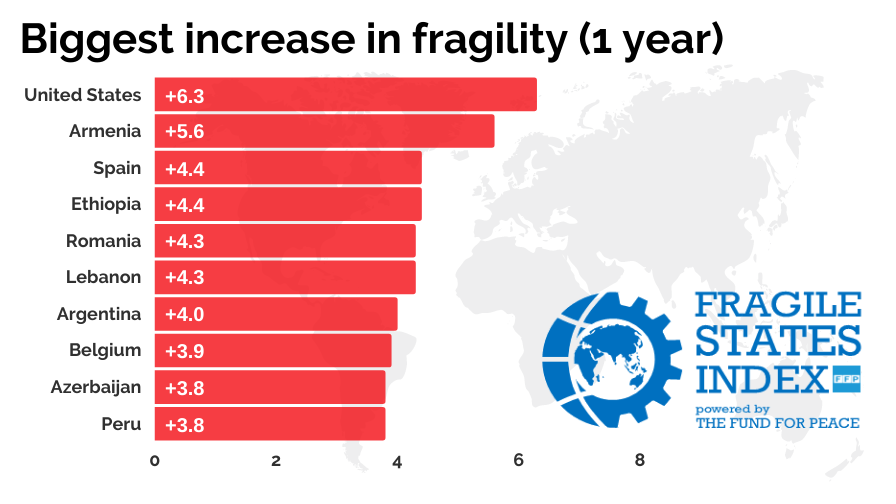

MOST WORSENED COUNTRIES

The country which saw the largest year-on-year worsening in their total score in the 2021 FSI is the United States. Over the past year, the US saw the largest protests in the country’s history in response to police violence which were often met by a heavy-handed state reaction along with sustained efforts to delegitimize the election process, which escalated violently in early 2021. Despite the country’s abundant material wealth and an advanced health system, political polarization, a lack of social cohesion, Congressional gridlock, and misinformation contributed to a failed response that left over 350,000 dead by the end of the year and a steeper contraction in GDP than any time in the past 60 years.

The country which saw the largest year-on-year worsening in their total score in the 2021 FSI is the United States. Over the past year, the US saw the largest protests in the country’s history in response to police violence which were often met by a heavy-handed state reaction along with sustained efforts to delegitimize the election process, which escalated violently in early 2021. Despite the country’s abundant material wealth and an advanced health system, political polarization, a lack of social cohesion, Congressional gridlock, and misinformation contributed to a failed response that left over 350,000 dead by the end of the year and a steeper contraction in GDP than any time in the past 60 years.

The second most worsened country is Armenia, which suffered a devastating defeat in a brief but bloody conflict against neighboring Azerbaijan that was followed by widespread protests against Prime Minister Pashinyan. Armenia also reported the 19th-highest number of COVID deaths per capita as of the end of 2020. The third most worsened country is Ethiopia, where the postponement of general elections generated increased tension between the central government and the Tigray region which spiraled into a civil war in which the central government has been heavily supported by the Eritrean military and which has been characterized by human rights abuses. 2020 also saw a shocking increase in violence in Benishangul-Gumuz, as well as significant increases in the Oromia, SNNP, and Somali regions.

Among the other most worsened countries on a year-on-year basis, many of them unsurprisingly were severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, including Spain, Romania, Argentina, Peru, Croatia, Czechia, and Hungary. However, it was Belgium that saw far and away the highest per capita rate of reported deaths due to COVID-19, over 30% higher than that of the next highest rate, by the end of the year. Many of these countries also experienced sharp economic contractions along with lockdowns that disrupted the provision of public services. The 2021 list of most worsened countries is rounded out by Lebanon, where political dysfunction set the stage for a massive explosion in the port of Beirut and the economy contracting by an astonishing 25 percent, and Azerbaijan, which was heavily supported by Turkey in its victorious war with Armenia and which now must re-incorporate territories which have been held under de facto Armenian control since 1994.

Over the past decade, the top 5 most worsened countries remain Libya, Syria, Mali, Venezuela, and Yemen, all of which have experienced conflict and/or economic collapse during that period. Among the next five, however, only Mozambique has seen significant levels of violent conflict. The other four are instead marked more by increased group grievance and polarization. In Brazil, corruption convictions against popular former president Lula da Silva were annulled by the Supreme Court in March 2021, opening the way for him to run against divisive President Bolsonaro in 2022. In Bahrain, divisions between the Sunni royal family and its supporters on the one side and the Shia-majority population and the political opposition on the other have widened in recent years. Like the United States, the United Kingdom has seen increasingly entrenched political polarization and a rise in group grievances.

MOST IMPROVED COUNTRIES

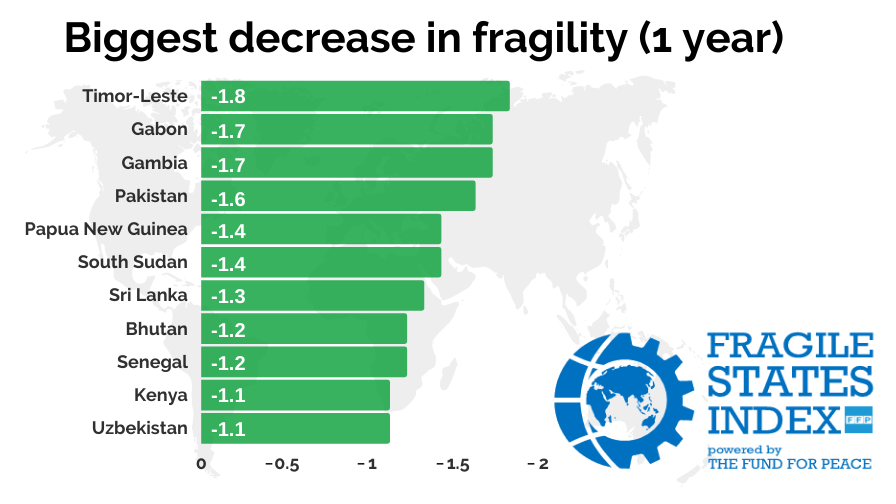

The country which experienced the largest improvement in its total score on the 2021 FSI is Timor-Leste. One of the youngest countries in the world, Timor-Leste has seen a steady long-term trend of improvement for over a decade and in 2020 the country demonstrated its increased resilience, recording no confirmed deaths from COVID-19 over the entire year. While the country, which is heavily dependent on oil revenues, did see a sharp economic contraction, proactive unified political action together with broad social solidarity have produced impressive results in containing the pandemic. The second most improved country was The Gambia, which has also continued a sustained trend of improvement beginning with FSI 2018.

The country which experienced the largest improvement in its total score on the 2021 FSI is Timor-Leste. One of the youngest countries in the world, Timor-Leste has seen a steady long-term trend of improvement for over a decade and in 2020 the country demonstrated its increased resilience, recording no confirmed deaths from COVID-19 over the entire year. While the country, which is heavily dependent on oil revenues, did see a sharp economic contraction, proactive unified political action together with broad social solidarity have produced impressive results in containing the pandemic. The second most improved country was The Gambia, which has also continued a sustained trend of improvement beginning with FSI 2018.

Those countries which have seen the largest improvements over the past ten years continue to be the result of steady improvement over that timeframe that often goes largely unnoticed, led by Cuba, Bhutan, and Uzbekistan. Also among the ten most improved over the decade are Indonesia and Timor-Leste, tied for sixth most improved, demonstrating the success the two neighbors have had in moving past their history of conflict. Finally, Vietnam, which had the tenth largest improvement in its total score in the last ten years, demonstrated impressive resilience during 2020, recording just 35 confirmed deaths due to COVID-19 and achieving economic growth of 2.9%, 8th fastest in the world.

A WORD ABOUT RANKINGS

Seventeen years ago, when the first edition of what was then called the Failed States Index was published in Foreign Policy magazine, much of the emphasis and attention was focused on the rankings, on who was first and who was last. However, over a decade-and-a-half later, now armed with 17 years of trend data, the discourse is fortunately far more nuanced, with a focus on trends and rate-of-change and with attention paid to a country’s individual indicator scores instead of only its total composite score.

Nevertheless, the temptation to rank countries — particularly wherever quantitative data is involved — is nearly inescapable. This year, Yemen once more claimed the top position, for the third year in a row, as a result of its continuing civil war and humanitarian catastrophe. Meanwhile, at the other end of the Index, Finland has ranked as the world’s least fragile state for more than a decade (when it first overtook its neighbor, Norway). Though there may be some level of interest in who is first and who is worst, ultimately such an observation does not offer particular insight into the specific areas of fragility and resilience within each of the 179 countries that we assess on an annual basis.

* * *

The publication of the 2021 FSI provides an opportunity to take a step back and reflect on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic thus far. One thing that has been abundantly clear and is reflected on this year’s FSI is that a shock – whether it be a recession, a natural disaster, or a pandemic – are rarely discrete and isolated challenges. An economic shock is not just an economic crisis. A conflict is not just a security crisis. . And COVID-19 has not just been a health crisis. Preparing for (or responding to) a pandemic as a health challenge alone is insufficient and only increases the likelihood of failure. Resilience to any shock requires broader, inter-dimensional capacity. The COVID-19 pandemic has had economic, political, and social effects. These have also had ensuing effects in a cascading series that has and will have far reaching consequences, many of which are still impossible to predict, as countries around the world struggle to recover, regain lost ground, and prepare for the next emergency.

The past year has also, however, starkly demonstrated the limits of our collective attention. While COVID-19 dominated headlines and airwaves, other crises erupted, such as conflict in the Caucasus. Yet when our attention wandered away from the pandemic, we found countries and our communities afflicted by a second, a third, a fourth wave.

In addition to helping guide our reflection on the past, the FSI can also help inform how we move forward over the next year, the next decade, and beyond. The 2021 FSI was heavily influenced by which countries were able to contain COVID-19 and which saw it spread almost unchecked. Next year the focus will turn to the capacities and constraints faced by countries as they seek to vaccinate their people and transition to a robust and inclusive recovery. The FSI can also help provide an understanding of the structural vulnerabilities uncovered this past year, informing how best to prepare for and manage the next crisis.

Image from Martin Sanchez under the Unsplash license.