BY J.J. MESSNER DE LATOUR

As many countries continue to suffer thousands of deaths and millions experience social isolation and economic hardship due to the COVID-19 crisis, the 2020 Fragile States Index (FSI) will not provide any data or analysis of how the crisis is affecting the social, economic, and political fortunes of the 178 countries it measures. For some who are experiencing COVID-19 fatigue, perhaps this will come as an enormous relief.

Perhaps one of the most limiting aspects of an annual index is that it is by definition retrospective. By the time the numbers are crunched, the data is analyzed, and all the fancy graphics are published, something new and unexpected has captured the public’s attention and the findings of the index no longer seem particularly relevant.

Indeed, the 2012 Fragile States Index (FSI) was published just as Middle Eastern and North African nations were in the grips of the Arab Spring – the FSI assessment period for the preceding year had closed only 13 days after Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor, set himself on fire in response to police abuse, igniting an Arab Spring that would soon consume wide swaths of North Africa and the Middle East. The FSI was released with barely a register of the revolutions to come, just as the eyes of the world were focused on mass protests spreading rapidly across Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen. Now, with COVID-19 pandemic, there is a sense of déjà vu for the FSI, as the crisis that currently grips the world is not explicit in the current FSI data.

However, this is not to say the FSI tells us nothing about the present or the future.

The utility of data sets such as the FSI is not found in simply reflecting the CNN ticker back to us. The FSI does not add much value in telling us that Yemen, Somalia, Syria, or Libya are fragile states. It is most definitely not helpful in telling us that Scandinavian countries are generally extremely stable. And today, the FSI would not have added much value in measuring COVID-19’s impacts in the middle of an unfolding crisis. Rather, it is the long-term trends of the FSI that are uniquely helpful in guiding policy makers and implementers on understanding where risk exists and is increasing, or where quiet, steady improvement is marching forward.

Looked at in this way, the Index can be used to shed light on the context in which a crisis such as the Arab Spring, the COVID 19 Pandemic, or any other shock or potential emergency might take place. In a situation of high demographic pressures, for example, how will the country manage the extra stress on their health systems? In a situation of high group grievance, how will society mobilize the necessary collective effort to respond?

Looked at in this way, the Index can be used to shed light on the context in which a crisis such as the Arab Spring, the COVID 19 Pandemic, or any other shock or potential emergency might take place. In a situation of high demographic pressures, for example, how will the country manage the extra stress on their health systems? In a situation of high group grievance, how will society mobilize the necessary collective effort to respond?

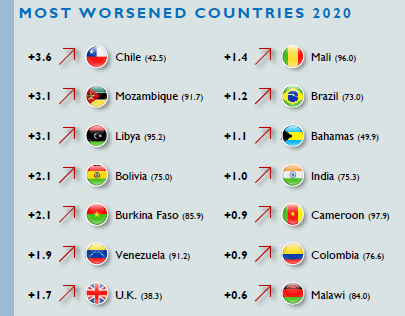

MOST WORSENED COUNTRIES

The most-worsened country in the 2020 FSI is Chile, a remarkable turnaround for a country that had otherwise been demonstrating steady gains to previously rank within the 30 most stable countries on the Index. However, recent protests over economic and social inequality, met with heavy-handed government responses, highlighted underlying vulnerabilities that had served to undermine the durability of Chile’s recent improvements. The second most worsened country for 2020 is Mozambique – which also rates as the sixth most worsened country over the past decade of the FSI – in the wake of severe natural disasters that exposed the country’s long unaddressed vulnerabilities and sparking renewed conflict in the north of the country.

Among the other most worsened countries for 2020, Libya, Burkina Faso, and Mali saw a continuation of conflict and violence that has wracked each of those countries for a prolonged period; Bolivia, Brazil and Venezuela witnessed political instability and questionable leadership; Colombia’s peace agreement continued to unravel; the Bahamas were hit by natural disaster; and India and Cameroon saw increased repression of, and violence against, minority groups. Another notable case was the United Kingdom, which continued its long-term worsening trend as Brexit reached its crescendo, leaving the country to rate as the seventh most worsened on the index.

Among the other most worsened countries for 2020, Libya, Burkina Faso, and Mali saw a continuation of conflict and violence that has wracked each of those countries for a prolonged period; Bolivia, Brazil and Venezuela witnessed political instability and questionable leadership; Colombia’s peace agreement continued to unravel; the Bahamas were hit by natural disaster; and India and Cameroon saw increased repression of, and violence against, minority groups. Another notable case was the United Kingdom, which continued its long-term worsening trend as Brexit reached its crescendo, leaving the country to rate as the seventh most worsened on the index.

Over the long-term, the most worsened countries of the past decade come as no surprise, as Libya, Syria, Mali, Yemen, and Venezuela have continued to unravel amidst varying levels of protracted conflict and instability. Though it would be easy to assume that the most worsened countries of the FSI are either lesser-developed or the scene of conflict (or both), the Top 20 most worsened since 2010 includes the United Kingdom and the United States, both of which have experienced years of tumultuous politics and social division.

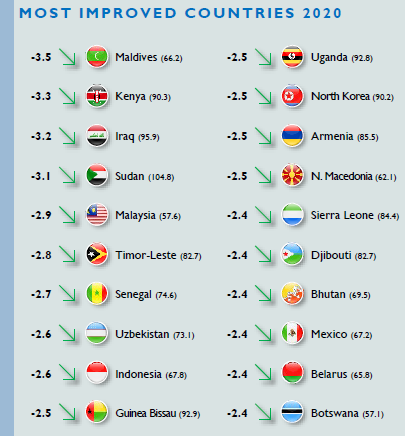

MOST IMPROVED COUNTRIES

Meanwhile, the most-improved country in 2020 is the Maldives, which continued a long-term trend of near-constant improvement that has seen the country move from being ranked 66th in 2007 (when it was first included in the FSI) to 99th in 2020. Three countries – Sudan, Iraq, and Kenya – tied for second most improved country in 2020, all improving from previous bouts of conflict, instability, and repression. By no means should any of these three countries be considered as necessarily more stable – after all, they rank 8th, 17th, and 29th respectively on the FSI – however such gains should be cause for cautious optimism and representative of tentative steps on a positive path.

Meanwhile, the most-improved country in 2020 is the Maldives, which continued a long-term trend of near-constant improvement that has seen the country move from being ranked 66th in 2007 (when it was first included in the FSI) to 99th in 2020. Three countries – Sudan, Iraq, and Kenya – tied for second most improved country in 2020, all improving from previous bouts of conflict, instability, and repression. By no means should any of these three countries be considered as necessarily more stable – after all, they rank 8th, 17th, and 29th respectively on the FSI – however such gains should be cause for cautious optimism and representative of tentative steps on a positive path.

Unlike the most worsened countries, the most improved over the past decade have not been headline grabbers, as countries like Cuba, Georgia, Uzbekistan and Moldova have made quiet, consistent improvement over time. Though, it must be viewed within the broader context that it is more likely that a country is able to make significant gains if its starting point is well behind that of its peers. It is therefore likely no accident that six of the ten most improved are former Soviet states (Georgia, Uzbekistan, Moldova, Belarus, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyz Republic).

A WORD ABOUT RANKINGS

Sixteen years ago, when the first Failed States Index was published in Foreign Policy magazine, much of the emphasis and attention was focused on the rankings. The question was invariably, ‘who is the world’s most failed state?’ However, a decade-and-a-half later, now armed with 16 years of trend data, the discourse is fortunately far more nuanced and now the focus is much more on trends and rate-of-change — and, more importantly, measuring a country’s performance over time against itself rather than against its peers.

Sixteen years ago, when the first Failed States Index was published in Foreign Policy magazine, much of the emphasis and attention was focused on the rankings. The question was invariably, ‘who is the world’s most failed state?’ However, a decade-and-a-half later, now armed with 16 years of trend data, the discourse is fortunately far more nuanced and now the focus is much more on trends and rate-of-change — and, more importantly, measuring a country’s performance over time against itself rather than against its peers.

Nevertheless, the temptation to rank countries — particularly wherever quantitative data is involved — is nearly inescapable. This year, Yemen again claimed the top position as a result of its continuing civil war and humanitarian catastrophe. Meanwhile, at the other end of the Index, Finland has ranked as the world’s least fragile state for the tenth year in a row (when it first overtook its neighbor, Norway). Though there may be some level of interest in who is first and who is worst, ultimately such an observation is largely meaningless in terms of giving any degree of insight on specific strengths and vulnerabilities, nuance, let alone long-term trends, of the 178 countries that we assess annually.

* * *

Looking forward to 2021, there is little doubt the FSI will be dominated by the social, economic, and political fallout of COVID-19. It is highly likely that some of the countries most heavily impacted so far – such as China, the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Italy – will register significantly increased pressure. As the impacts of the pandemic, both direct and indirect, filter through the global system it is equally likely that much of the world will be affected – more so should the crisis worsen, or if there are additional waves of the pandemic in months to come.

Nevertheless, it will be important in the longer-term to understand the deeper societal vulnerabilities that the crisis has uncovered, and data will be critical in being able to tell that story soberly. It is only through a sober and critical evaluation of the underlying vulnerabilities that COVID-19 is laying bare globally, will we be able to rise above the justifiable panic accompanying coverage of the pandemic to understand how we recover and, perhaps more importantly, plan and prepare for the inevitable next crisis.