BY NATALIE FIERTZ

At the beginning of the 21st century, Hungary and Poland were frequently lauded as two of the most successful examples of democratic transitions, emerging from the shadow of communist dictatorships and joining the Euro-Atlantic community through membership in organizations such as NATO and the European Union.[1] Today the two countries are again often mentioned together, but now as vanguards of rising illiberal populism and democratic deterioration. The similar trajectories of the two countries is reflected in the trend of several of the Fragile States Index’s (FSI) component indicators, most notably Group Grievance and Human Rights and Rule of Law.

The two countries’ embrace of unconstrained majoritarianism has occurred over different timeframes. In Hungary, Viktor Orban, once upon a time a champion of liberalism in Hungary’s struggle for freedom but now an admirer of the likes of Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, led his Fidesz party to a two-thirds parliamentary majority in 2010 giving him unchecked power to rewrite the constitution. He used that power to enact sweeping changes to the Hungarian system of government including overhauling the Constitutional Court to give Fidesz appointees a majority, eliminating the independent Fiscal Council, gerrymandering legislative districts, and gutting the independent press. In total, Orban and Fidesz passed more than 1,000 laws in their first five years, including a new constitution and a series of amendments, some of which had previously been deemed unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court.[2]

The end of those five years saw the election of Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland, which won an absolute majority in the Sejm, the Polish Parliament, the first in Poland’s post-communist history. Ahead of those elections, PiS had employed a vocabulary similar to that used by Fidesz, focusing on accusations that the ruling party had overseen a failed economy, embraced alien cosmopolitan liberal values, and failed to sufficiently purge communists and their collaborators. After their ascent to power, PiS’s initial moves mirrored those enacted by Fidesz, as the government moved to pack the Constitutional Tribunal with its own appointees and assert control over public broadcasters, purging them of dissidents. The new government also passed notably illiberal laws including the criminalization of discourse on Polish complicity in the Holocaust as well as a law giving the security services sweeping powers over telecommunications and personal information. The latter is written in vague terms, giving a government that often labels its political opponents as traitors wide latitude in determining what constitutes an act of terrorism in a country that has not experienced any such acts whatsoever since the fall of the Soviet Union.[3]

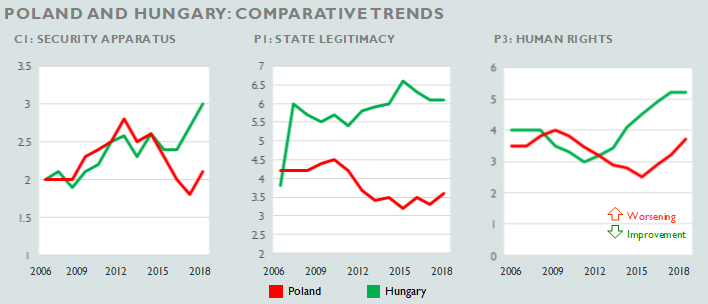

The similar tactics employed by Fidesz and PiS are reflected in their scores and trends on the FSI Human Rights & Rule of Law indicator, wherein the two countries experienced a worsening of 1.1 and 1.2 points, respectively, in the four years after their assumption of power. This worsening has been mirrored by the deterioration of Hungary’s and Poland’s score on a wealth of metrics of institutional quality and rule of law from across the ideological spectrum, including Freedom House’s Freedom in the World, the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, and the Cato Institute’s Human Freedom Index.

There has been a range of explanations proffered to explain the rise of illiberal majoritarian populism in Poland and Hungary, both by supporters and members of the two regimes as well as by outside observers. Some of the most frequently cited include the oppressive yoke of the European Union, the influx of refugees from Syria and other countries, and the inadequate response of the existing system to rising inequality and the financial crisis. There are likely grains of truth in each. Poland, however, has been the largest recipient of EU structural funds, with an allocation of around €80 billion for 2014-2020, and the structural funds allocated to Hungary represent the highest proportion of its GDP of any EU member state, at over 3%.[4] The degree to which refugee inflows were a genuine catalyst is arguable – the spike in refugees arriving in Hungary did not begin until 2013, three years after Fidesz began implementing its illiberal agenda, while asylum application in Poland peaked in the same year and had declined by around 20% by 2015 when PiS was elected.[5]

In early 2015, Poland’s economic performance was generating talk of a new golden age for the country. Since 1989, it had grown faster than all other large economies at a similar level of development and more than doubled its GDP per capita. and a poll found that more than 80% of Poles were satisfied with their lives.[6] The FSI Uneven Development indicator also shows steady improvement by both countries and World Bank estimates of the GINI Index suggests inequality in Poland had been declining through 2014 while inequality in Hungary hit a nadir in the year before Fidesz was elected and has increased since then.

One commonality between the two countries revealed by the FSI is the steady worsening in the Group Grievance indicator. While there has been some divergence in the last two years, both countries have seen fairly consistent annual increases in their score. While the score alone does not indicate the cleavages along which these grievances grew, both countries have seen an increase in nationalist rhetoric and actions even before the refugee crisis including, in Hungary’s case, lamenting the loss of territory in the treaties that ended World War I.

With governing parties in countries such as Austria and the Czech Republic showing similarities to the authoritarian instincts of Fidesz and PiS, Poland and Hungary may be only the beginning of a troubling trend in Europe.

ENDNOTES

1. Freedom House. 2004. Nations in Transit.

2. Zlatko Grgić. 2018. “As West Fears the Rise of Autocrats, Hungary Shows What’s Possible” New York Times, February 10.

3. Freedom House. “Modern Authoritarianism: Illiberal Democracies” URL at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/modern-authoritarianism-illiberal-democracies.

4. Michael Peel and Alex Barker. 2017. “Putting a price on the rule of law” Financial Time, November 13.

5. Eurostat. “Asylum and first time asylum applicants by citizenship, age and sex Annual aggregated data”

6. Marcin Piatkowski. 2015. “How Poland Became Europe’s Growth Champion” The Brookings Institution, February 11.