BY J.J. MESSNER

It certainly felt like a tumultuous year in 2017. As the wars in Syria and Yemen ratcheted up in intensity, Qatar was suddenly politically, economically and physically isolated from its neighbors, Catalonia moved forward on its attempts to separate from Spain, Venezuela fell further into chaos, the United Kingdom continued to struggle with the terms of its exit from the European Union, and the United States (in addition to being plagued by a series of natural disasters) moved from one political crisis to the next. Yet despite all of these concerns, the clear message of the Fragile States Index (FSI) in 2018 was that, on the whole, most countries around the world continue to show signs of steady improvement, and many – particularly Mexico – demonstrate resiliency in the face of enormous pressure. Nevertheless, as much as we tend to (rightly) focus on the world’s trouble spots whenever we talk of state fragility, perhaps the clearest message of the 2018 FSI is that pressures can affect all states – even the world’s richest and most developed.

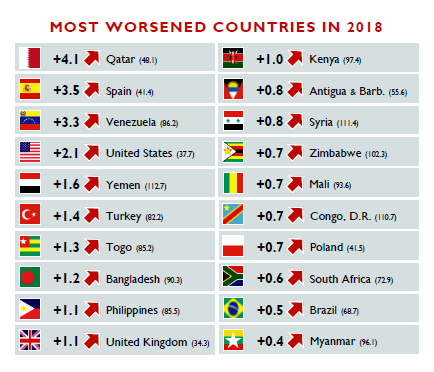

MOST WORSENED COUNTRIES IN 2018

A frequent criticism of the Fragile States Index in the past has been that it is somehow biased against the world’s poorest countries. Yet the most-worsened country for 2018 is Qatar, the world’s wealthiest country per capita. Though the country’s considerable wealth has no doubt cushioned the blow, the move by regional neighbors Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates to impose a political and economic blockade on the small Gulf nation has exacted a significant toll on Qatar’s stability. The full financial and political impacts of the blockade – which remains in place – are likely yet to be fully realized. Indeed, there is widespread concern that the move against Qatar by its neighbors may only be the beginning of a longer-term campaign by regional adversaries to undermine the al Thani family’s reign over the country, a threat made greater by the apparent (and very public) political abandonment of Qatar by a purported ally, the United States.

A frequent criticism of the Fragile States Index in the past has been that it is somehow biased against the world’s poorest countries. Yet the most-worsened country for 2018 is Qatar, the world’s wealthiest country per capita. Though the country’s considerable wealth has no doubt cushioned the blow, the move by regional neighbors Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates to impose a political and economic blockade on the small Gulf nation has exacted a significant toll on Qatar’s stability. The full financial and political impacts of the blockade – which remains in place – are likely yet to be fully realized. Indeed, there is widespread concern that the move against Qatar by its neighbors may only be the beginning of a longer-term campaign by regional adversaries to undermine the al Thani family’s reign over the country, a threat made greater by the apparent (and very public) political abandonment of Qatar by a purported ally, the United States.

Similarly, three of the ten most-worsened countries for 2018 are also among the world’s most developed: Spain, the United States, and the United Kingdom, who are each experiencing deep internal political divisions, albeit for different reasons. This provides clear evidence that stability cannot be taken for granted and can affect developed and developing countries alike. Though such developed countries have the significant benefit of higher levels of capacity and resilience that more fragile countries tend to lack, sharp and sustained increases in pressures should not be ignored.

As the second-most worsened country in 2018, Spain was hit by increased internal instability as the Catalonia region held an independence referendum that was, arguably, met by a cack-handed response by the central government in Madrid that likely intensified the problem. As the Spanish state sought to crack down on the separatist referendum – even resorting to violence in some cases – support for a separate Catalan state appeared to surge in defiance of Madrid’s response. Though Catalan separatist sentiment has been simmering for some time, 2017 may come to be seen as a turning point – and, potentially, a point of no return for the Spanish state. In the longer term, a future disintegration of Spain could threaten to not only have more widespread consequences internally (since Catalonia is not the only region in Spain to harbor separatist tendencies) but may lead to an emboldening of other regional disintegration throughout Europe.

The United States has experienced significant political upheaval recently, and as a result has ranked as the fourth most-worsened country for 2018. Despite a remarkably strong economy, this economic success has been largely outweighed by social and political instability. However, we must be careful not to misunderstand the longer-term nature of this trend. Though some critics will likely be tempted to associate the worsening situation in the United States with the ascendance of President Trump, and what can generously be described as his Administration’s divisive leadership and rhetoric, the reality is that the pressures facing the United States run far deeper. Many “inside the Beltway” in Washington have long complained of a growing extremism in American society and politics, with an increasingly disenfranchised (if not vanishing) political center. The FSI demonstrates that this is no illusion – it is definitely happening. Indeed, on the ten-year trend of the three Cohesion Indicators (including Security Apparatus, Factionalized Elites, and Group Grievance), the United States is the most-worsened country in the world bar none, ahead of the likes of Libya, Bahrain, Mali, Syria, South Africa, Tunisia, Turkey, and Yemen. To be sure, the United States has nearly unparalleled capacity and resiliency, meaning that there is little risk that the country is about to fall into the abyss. Nevertheless, these findings should serve as a wake-up call to America’s political leaders (not to mention media influencers) that divisive policy-making and rhetoric that seeks to divide Americans for political gain can have very real consequences and can threaten the country’s long-term stability and prosperity.

Though the challenges facing the United Kingdom are different to the United States, the two countries have nevertheless been facing a remarkably similar long-term trendline, wherein the United Kingdom is the third-most worsened country in the world for those same three Cohesion Indicators since 2013. As described in last year’s FSI, the Brexit referendum came amidst unprecedented levels of division and group grievance among Britain’s social and political sphere. While the painful – and seemingly near-impossible – Brexit negotiations carry on toward the country’s planned exit from the European Union in 2019, the FSI provides a similar lesson to British leaders and influencers as it does for their American counterparts – that even for a developed nation, divisive policy-making and rhetoric is simply incompatible with a country’s ability to thrive.

Among the other most-worsened countries for 2018, it probably comes as little surprise that Yemen and Syria, both mired in prolonged civil conflicts, continue to worsen. Both countries are now firmly entrenched among the top four countries of the Index, along with Somalia and South Sudan who have also been witness to long periods of conflict. Rounding out the most worsened countries, Venezuela ranks as the third most-worsened country in 2018 as the country spirals into chaos under the epic mismanagement of Nicolas Maduro’s government that is equally further tightening its grip on power, closing civil space and silencing political opposition. Venezuela now boasts the unfortunate distinction of being the second-most fragile country in the Western Hemisphere, behind Haiti. Two other countries under the leadership of increasingly authoritarian presidents, namely Recep Tayyap Erdogan in Turkey and Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, also continue to worsen significantly. And though South Africa also continues to worsen as a result of former President Jacob Zuma’s disastrous administration, the resignation of Zuma and the election of Cyril Ramaphosa as the Head of the African National Congress Party, and hence President of the Republic, has at least provided a glimmer of hope that South Africa’s woes may soon take a turn for the better.

Of particular concern among the most-worsened countries for 2018 is Poland. Although Poland’s worsening of 0.7 points since 2017 is not of the same magnitude of some other countries, its longer-term trend is of the utmost concern, not only for Poland but for Europe more generally. As Hungary’s government of Viktor Orban has become increasingly illiberal, Poland appears to be following a startlingly similar trend line to Hungary, albeit on a 4- to 5-year delay. As the situation in Poland develops, and the Eastern European region more generally demonstrates greater illiberal tendencies, the similar trends of Hungary and Poland may provide a critical case study into early warning.

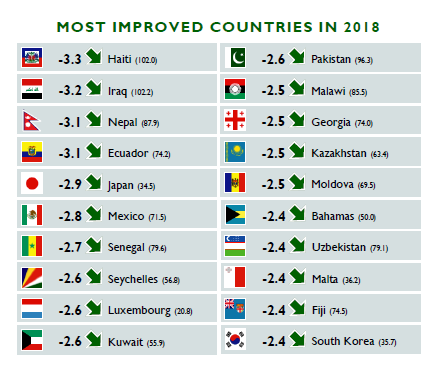

MOST IMPROVED COUNTRIES IN 2018

Of the 178 countries assessed by the Fragile States Index, 151 demonstrated at least marginal improvement. Certainly, there remains significant fragility and instability in many different parts of the world, but overall most countries continue to move upwards on a trajectory of positive development. As the long-term trends of the FSI have shown, a country can still be fragile and yet improving. Nevertheless, this trend of improvement will not always be linear, and may be a case of constantly moving two steps forward and one step back.

Of the 178 countries assessed by the Fragile States Index, 151 demonstrated at least marginal improvement. Certainly, there remains significant fragility and instability in many different parts of the world, but overall most countries continue to move upwards on a trajectory of positive development. As the long-term trends of the FSI have shown, a country can still be fragile and yet improving. Nevertheless, this trend of improvement will not always be linear, and may be a case of constantly moving two steps forward and one step back.

In the 2017 Fragile States Index, Mexico (along with Ethiopia) was the most-worsened country for the preceding year, fueled by economic concerns, widespread violence, and heightened uncertainty over its relations with the United States, underlined by harsh rhetoric from then-newly elected President Trump and policy objectives that threatened to isolate Mexico from its neighbor and largest trading partner. However, in 2018, Mexico has rebounded, lurching from most-worsened in 2017 to sixth most-improved in 2018. Much of this improvement has been driven by economics – despite the threat to its economy emanating from the United States, Mexico has worked to diversify its trade relationships throughout Latin America and with Europe. Meanwhile, the country has experienced significantly less pressure from Central American migrants transiting through Mexico to its northern border, partly through improved policy and international assistance, but also potentially due to a fall in interest among migrants to attempt to enter the United States. Though Mexico continues to experience significant domestic pressures – bound to be worsened by this year’s contentious presidential election and the chance that firebrand populist and perennial candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador may emerge victorious – the country has nevertheless demonstrated significant resiliency.

It may come as a surprise to see countries such as Iraq and Haiti – both ranked 11th and 12th respectively on the Fragile States Index – as the most-improved for 2018. However, again, the FSI demonstrates clearly that a country experiencing high levels of fragility can nevertheless improve over time. Both Haiti and Iraq continue to experience high levels of instability and variously, poverty and conflict. However, the situation in both countries appears to be better than it was 12 months ago – in Haiti’s case as a disputed election was resolved with minimal conflict and the country continued its path to recovery from the ruinous earthquake of 2010; in Iraq’s case as significant victories were recorded against Daesh, and relative stability returned to some recently conflicted parts of the country. Nevertheless, both countries remain highly unstable, and could all too easily slip back and lose the gains of 2017.

LOOKING AHEAD

As we enter into 2018, conflict continues to rage – and worsen – in Syria and Yemen. The signs of continued instability and potential conflict in many parts of the world continue, from saber-rattling in North Korea to the threat of terrorism in the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin. Fractious politics in the United States, United Kingdom, and parts of Europe continue to threaten to destabilize otherwise stable, developed, and prosperous nations. And Qatar remains isolated, politically and economically, unclear on whether the embargo may end soon or if the embargo may simply be the opening salvo of a deeper, longer regional conflict.

Though the FSI does not predict unrest or turmoil, it does provide early warning of the conditions that can give rise to instability – but even then, someone has to do something with that information. It is therefore incumbent upon policy-makers, influencers, and practitioners to understand and heed the warnings of short- and long-term trends, to be mindful of the growing potential for the conditions of instability, and to take action to prevent or mitigate such deterioration. But as much as the world may overall be improving, more than anything else the FSI demonstrates that stability can never be taken for granted – even in the world’s richest and most developed countries.